Productivity: More with Less by Better

Available resources are scarce. To sustain our society's income and living standards in a world with ecological and demographic change, we need to make smarter use of them.

Dossier

In a nutshell

Nobel Prize winners Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus state in their classic economics textbook: Economics matters because resources are scarce. Indeed, productivity research is at the very heart of economics as it describes the efficiency with which these scarce resources are transformed into goods and services and, hence, into social wealth. If the consumption of resources is to be reduced, e. g., due to ecological reasons, our society’s present material living standards can only be maintained by productivity growth. The aging of our society and the induced scarcity of labour is a major future challenge. Without productivity growth a solution is hard to imagine. To understand the processes triggering productivity growth, a look at micro data on the level of individual firms or establishments is indispensable.

Our experts

Department Head

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-708 Request per E-Mail

President

If you have any further questions please contact me.

+49 345 7753-700 Request per E-MailAll experts, press releases, publications and events on “Productivity”

Productivity is output in relation to input. While the concept of total factor productivity describes how efficiently labour, machinery, and all combined inputs are used, labour productivity describes value added (Gross Domestic Product, GDP) per worker and measures, in a macroeconomic sense, income per worker.

Productivity Growth on the Slowdown

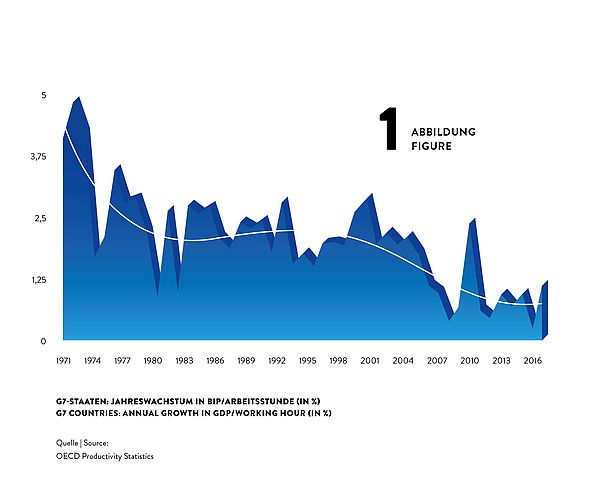

Surprisingly, despite of massive use of technology and rushing digitisation, advances in productivity have been slowing down during the last decades. Labour productivity growth used to be much higher in the 1960s and 1970s than it is now. For the G7 countries, for example, annual growth rates of GDP per hour worked declined from about 4% in the early 1970s to about 2% in the 1980s and 1990s and then even fell to about 1% after 2010 (see figure 1).

This implies a dramatic loss in potential income: Would the 4% productivity growth have been sustained over the four and a half decades from 1972 to 2017, G7 countries’ GDP per hour would now be unimaginable 2.5 times as high as it actually is. What a potential to, for instance, reduce poverty or to fund research on fundamentals topics as curing cancer or using fusion power!

So why has productivity growth declined dramatically although at the same time we see, for instance, a boom in new digital technologies that can be expected to increase productivity growth? For sure, part of the decline might be spurious and caused by mismeasurement of the contributions of digital technologies. For instance, it is inherently difficult to measure the value of a google search or another video on youtube. That being said, most observers agree that part of the slowdown is real.

Techno-Pessimists and Techno-Optimists

Techno-pessimists say, well, these new technologies are just not as consequential for productivity as, for instance, electrification or combustion engines have been. Techno-optimists argue that it can take many years until productivity effects of new technologies kick in, and it can come in multiple waves. New technology we have now may just be the tools to invent even more consequential innovations in the future.

While this strand of the discussion is concerned with the type of technology invented, others see the problem in that inventions nowadays may diffuse slowly from technological leaders to laggards creating a wedge between few superstar firms and the crowd (Akcigit et al., 2021). Increased market concentration and market power by superstar firms may reduce competitive pressure and the incentives to innovate.

Finally, reduced Schumpeterian business dynamism, i.e. a reduction in firm entry and exit as well as firm growth and decline, reflects a slowdown in the speed with which production factors are recombined to find their most productive match.

While the explanation for and the way out of the productivity puzzle are still unknown, it seems understood that using granular firm level data is the most promising path to find answers.

What are the Origins of Productivity Growth?

Aggregate productivity growth can originate from (i) a more efficient use of available inputs at the firm level as described above or (ii) from an improved allocation of resources between firms.

Higher efficiency at the firm level captures, e.g., the impact of innovations (Acemoglu et al., 2018) or improved firm organisation (management) (Heinz et al., 2020; Müller und Stegmaier, 2017), while improved factor allocation describes the degree of which scarce input factors are re-allocated from inefficient to efficient firms (‘Schumpeterian creative destruction’) (Aghion et al., 2015; Decker et al., 2021).

Most economic processes influence the productivity of existing firms and the growth and the use of resources of these firms and their competitors as well. The accelerated implementation of robotics in German plants (Deng et al., 2020), the foreign trade shocks induced by the rise of the Chinese economy (Bräuer et al., 2019), but also the COVID-19 pandemic, whose consequences are still to evaluate (Müller, 2021) not only effects on productivity and growth of the firms directly affected but at the same time may create new businesses and question existing firms.

While productivity can be measured at the level of aggregated sectors or economies, micro data on the level of individual firms or establishments are indispensable to study firm organisation, technology and innovation diffusion, superstar firms, market power, factor allocation and Schumpeterian business dynamism. The IWH adopts this micro approach within the EU Horizon 2020 project MICROPROD as well as with the CompNet research network.

As “creative destruction” may also negatively affect the persons involved (e. g., in the case of layoffs, Fackler et al., 2021), the IWH analyses the consequences of bankruptcies in its Bankruptcy Research Unit and looks at the implications of creative destruction for the society, e. g., within a project funded by Volkswagen Foundation searching for the economic origins of populism and in the framework of the Institute for Research on Social Cohesion.

Publications on “Productivity”

Aufschwung bleibt moderat – Wirtschaftspolitik wenig wachstumsorientiert: Gemeinschaftsdiagnose Frühjahr 2016

in: Externe Monographien, 2016

Abstract

Die deutsche Wirtschaft befindet sich in einem moderaten Aufschwung. Das Bruttoinlandsprodukt dürfte in diesem Jahr um 1,6 Prozent und im kommenden Jahr um 1,5 Prozent zulegen. Getragen wird der Aufschwung vom privaten Konsum, der vom anhaltenden Beschäftigungsaufbau, den spürbaren Steigerungen der Lohn- und Transfereinkommen und den Kaufkraftgewinnen infolge der gesunkenen Energiepreise profitiert. Zudem ist die Finanzpolitik, auch wegen der zunehmenden Aufwendungen zur Bewältigung der Flüchtlingsmigration, expansiv ausgerichtet. Während die Bauinvestitionen ebenfalls merklich ausgeweitet werden, bleibt die Investitionstätigkeit der Unternehmen verhalten. Aufgrund der nur allmählichen weltwirtschaftlichen Erholung und der starken Binnennachfrage ist vom Außenhandel kein positiver konjunktureller Impuls zu erwarten. Die öffentlichen Haushalte dürften im Prognosezeitraum deutliche Überschüsse erzielen. Würden diese Handlungsspielräume wie bereits in den vergangenen Jahren wenig wachstumsorientiert genutzt, wäre das nicht nachhaltig.

Young, Restless and Creative: Openness to Disruption and Creative Innovations

in: NBER Working Paper, No. 19894, 2015

Abstract

This paper argues that openness to new, unconventional and disruptive ideas has a first-order impact on creative innovations—innovations that break new ground in terms of knowledge creation. After presenting a motivating model focusing on the choice between incremental and radical innovation, and on how managers of different ages and human capital are sorted across different firms with different degrees of openness to disruption, we provide firm-level, patent level and cross-country evidence consistent with this pattern. Our measures of creative innovations proxy for innovation quality (average number of citations per patent) and creativity (fraction of superstar innovators, the likelihood of a very high number of citations, and generality of patents). Our main proxy for openness to disruption is the age of the manager - based on the idea that only companies or societies open to such disruption will allow the young to rise up within the hierarchy. Using this proxy at the firm, patent and country level, we present robust evidence that openness to disruption is associated with more creative innovations, but we also show that once the effect of the sorting of young managers to firms that are more open to disruption is factored in, the (causal) impact of manager age on creative innovations is small.

Lessons from Schumpeterian Growth Theory

in: American Economic Review, No. 5, 2015

Abstract

By operationalizing the notion of creative destruction, Schumpeterian growth theory generates distinctive predictions on important microeconomic aspects of the growth process (competition, firm dynamics, firm size distribution, cross-firm and cross-sector reallocation) which can be confronted using rich micro data. In this process the theory helps reconcile growth with industrial organization and development economics.

Assessing European Competitiveness: The New CompNet Microbased Database

in: ECB Working Paper, No. 1764, 2015

Abstract

Drawing from confidential firm-level balance sheets for 17 European countries (13 Euro-Area), the paper documents the newly expanded database of cross-country comparable competitiveness-related indicators built by the Competitiveness Research Network (CompNet). The new database provides information on the distribution of labour productivity, TFP, ULC or size of firms in detailed 2-digit industries but also within broad macrosectors or considering the full economy. Most importantly, the expanded database includes detailed information on critical determinants of competitiveness such as the financial position of the firm, its exporting intensity, employment creation or price-cost margins. Both the distribution of all those variables, within each industry, but also their joint analysis with the productivity of the firm provides critical insights to both policy-makers and researchers regarding aggregate trends dynamics. The current database comprises 17 EU countries, with information for 56 industries, including both manufacturing and services, over the period 1995-2012. The paper aims at analysing the structure and characteristics of this novel database, pointing out a number of results that are relevant to study productivity developments and its drivers. For instance, by using covariances between productivity and employment the paper shows that the drop in employment which occurred during the recent crisis appears to have had “cleansing effects” on EU economies, as it seems to have accelerated resource reallocation towards the most productive firms, particularly in economies under stress. Lastly, this paper will be complemented by four forthcoming papers, each providing an in-depth description and methodological overview of each of the main groups of CompNet indicators (financial, trade-related, product and labour market).

Private Equity, Jobs, and Productivity

in: American Economic Review, No. 12, 2014

Abstract

Private equity critics claim that leveraged buyouts bring huge job losses and few gains in operating performance. To evaluate these claims, we construct and analyze a new dataset that covers US buyouts from 1980 to 2005. We track 3,200 target firms and their 150,000 establishments before and after acquisition, comparing to controls defined by industry, size, age, and prior growth. Buyouts lead to modest net job losses but large increases in gross job creation and destruction. Buyouts also bring TFP gains at target firms, mainly through accelerated exit of less productive establishments and greater entry of highly productive ones.