Electoral Credit Supply Cycles Among German Savings Banks

In this note we document political lending cycles for German savings banks. We find that savings banks on average increase supply of commercial loans by €7.6 million in the year of a local election in their respective county or municipality (Kommunalwahl). For all savings banks combined this amounts to €3.4 billion (0.4% of total credit supply in Germany in a complete electoral cycle) more credit in election years. Credit growth at savings banks increases by 0.7 percentage points, which corresponds to a 40% increase relative to non-election years. Consistent with this result, we also find that the performance of the savings banks follows the same electoral cycle. The loans that the savings banks generate during election years perform worse in the first three years of maturity and loan losses tend to be realized in the middle of the election cycle.

26. November 2015

In this note we document political lending cycles for German savings banks. We find that savings banks on average increase supply of commercial loans by €7.6 million in the year of a local election in their respective county or municipality (Kommunalwahl). For all savings banks combined this amounts to €3.4 billion (0.4% of total credit supply in Germany in a complete electoral cycle) more credit in election years. Credit growth at savings banks increases by 0.7 percentage points, which corresponds to a 40% increase relative to non-election years. Consistent with this result, we also find that the performance of the savings banks follows the same electoral cycle. The loans that the savings banks generate during election years perform worse in the first three years of maturity and loan losses tend to be realized in the middle of the election cycle.

The results are consistent with political interference in the credit policies of savings banks in Germany. It is consistent with a number of features of the governance of the savings banks, which are consistent with political interference.

- Local credit supply: German savings banks were stablished with the mandate to provide small and medium sized businesses with their financing needs, in order to support local business and employment. Savings banks are limited by law to lend only in their own local market, generally a city ("Stadtsparkasse") or a county ("Kreissparkasse").

- Prominent role of local politicians: Local politicians occupy prominent positions within the board of directors (Sparkassenverwaltungsrat) and also the central credit committee (Kreditausschuss) in their local savings bank. Based on county regulations, the chairman of both bodies is the political representative of the county, in most cases the mayor or the county commissioner (Landrat). The positions entail significant influence on lending decisions: At each savings bank, loans larger or riskier than a certain threshold need approval from the board members or the central credit committee. This set of tools enables the local politicians to follow their political motives via distorting banks' lending policies.

The local restriction of activities, combined with the substantial influence of local politicians on savings banks' credit decisions, suggest that the use of the banks for political purposes is possible. Our empirical results show that politicians actively make use of their position to their own political advantage by granting more loans and loans at more favorable terms in the year when elections in their community take place. The evidence is also consistent with evidence from politically controlled banks in other countries.1 The governance structure of German savings banks may hence induce political lending cycles, a misallocation of capital and also result in distortions of the electoral process.

Political Lending Cycles

Political business cycle theories describe politicians' incentives towards expansionary fiscal policies prior to the elections in order to increase their own popularity via better perceived economic conditions. Theories predict that politicians myopically try to reach the minimum unemployment rate at the onset of the elections, but when the election is over, they engage in deflationary policies to combat the consequent price surges (Nordhaus [1975]). We show that this behaviour also exists in German counties, where the local politicians use the savings banks' resources in order to engage in expansionary policies prior to the elections.

We use the balance sheet information of 452 German savings banks from 1995 till 2006 and combine it with county electoral data at the state level to study the differential lending behaviour of banks during election years and more importantly the performance of loans that are extended during the election period. The county elections in Germany are state-wide, i.e. all counties in one of the 16 German states hold elections at the same time. Throughout our sample period in each year, except for 2000 and 2005, there are elections in at least one and at most nine states. This cross-sectional and time series variation in election dates allows us to control for business cycle effects in Germany, because we can compare observations in states with elections to observations in states without. Moreover, by controlling for bank fixed effects, we compare each savings banks' credit supply in election years with its own credit supply in other years. We also control for time-varying regional economic conditions, namely debtper-capita growth and GDP-per-capita growth. This lets us control for common regional economic shocks and time trends. All the variables that we use in this study are defined as presented in Table 1. The summary statistics are presented in Table 2.

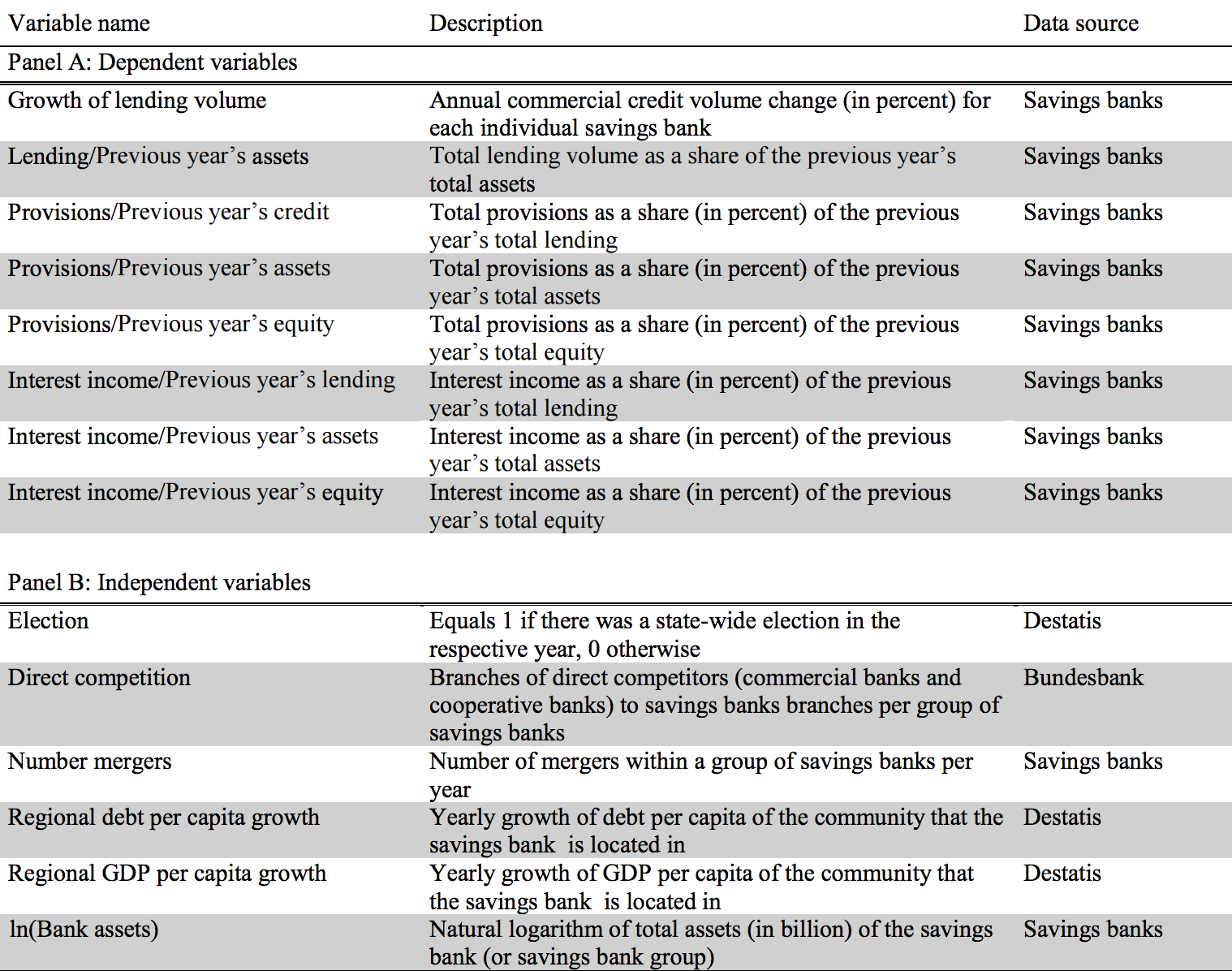

Table 1: Variable definitions

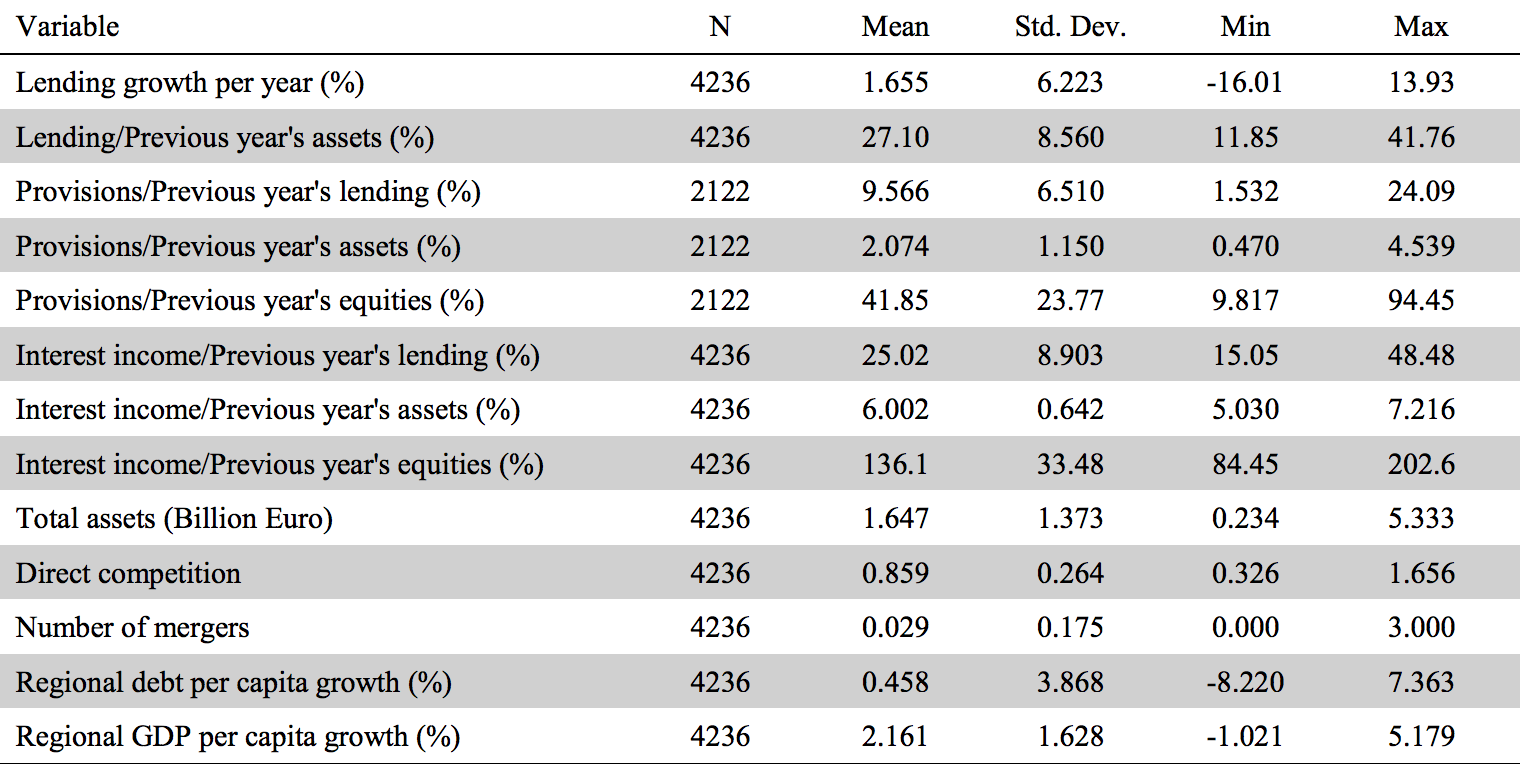

Table 2: Summary statistics

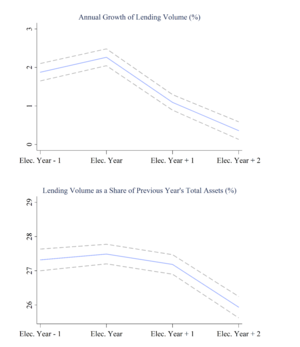

Figure 1: Lending during election cycles

Source: Own calculation by using German savings banks’ data

We start by plotting annual growth rate of total lending volume and lending volume as a share of last year's total assets for the electoral cycle.2 Figure 1 shows the annual growth rate of total lending for the election years, one year prior to the election and the two years after it.

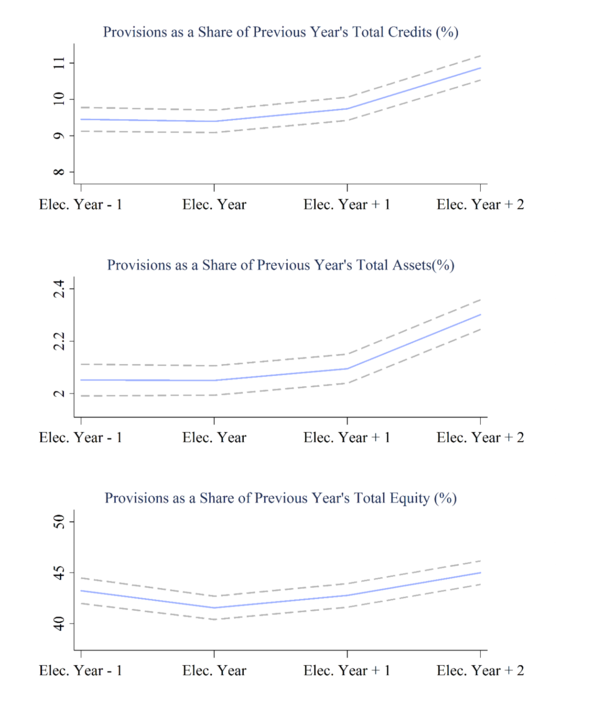

Figure 2: Loss provisions during election cycles

Source: Own calculation by using German savings banks’ data

In Figure 2, we do the same for total lending as a share of last year's total assets. Both these graphs show that during the election year, there is a sizeable increase in credit extended by local savings banks. In order to estimate the magnitude of the political lending effect, we run regressions of annual growth rate of total lending volume and lending volume as a share of last year's total assets on election year dummies and bank and regional-level control variables. The results are presented in Table 3. All specifications show a significantly positive coefficient for election years. To see how big such effects are, let's first consider the annual lending growth.

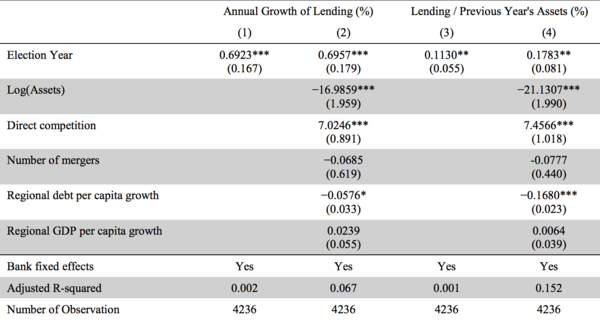

Table 3: Political lending cycle

Source: Own calculations by using German savings banks’ data

Here the most conservative estimate shows a 0.7 percentage points higher growth rate for lending during election years. From Table 2, we learn that the average annual growth rate of total lending is 1.65%. Therefore, the estimate tells us that during the election years, lending grows almost 40% faster than it grows in non-election years. Our estimates for lending as a share of total assets show that in election years, total lending as a share of total assets is about 0.17 percentage points higher than in normal years. Again, since we know that the average loan-to-assets ratio for savings banks is 27.1% and the size of the average bank is €1.65 billion, this estimate implies that during the election years, the average bank generates €7.6 million more loans in comparison to a non-election year.

Credit Quality

Loans granted based on favoritism frequently end up being of lower quality than loans which are generated in a competitive market.3 We find this to be the case in our setting as well: We provide evidence of credit quality cycles that also match the electoral cycle. First we examine how loss provisions4 of savings banks differ in the election year and the subsequent two years after the election in comparison to the year(s) prior to the election. If the loans generated during the election year are as safe as other loans, we should not see any systematic relationship of provisions with the electoral cycle. However, Figure 2 shows that loss provisions start to increase right after election years.

Figure 2: Loss provisions during election cycles

Source: Own calculation by using German savings banks’ data

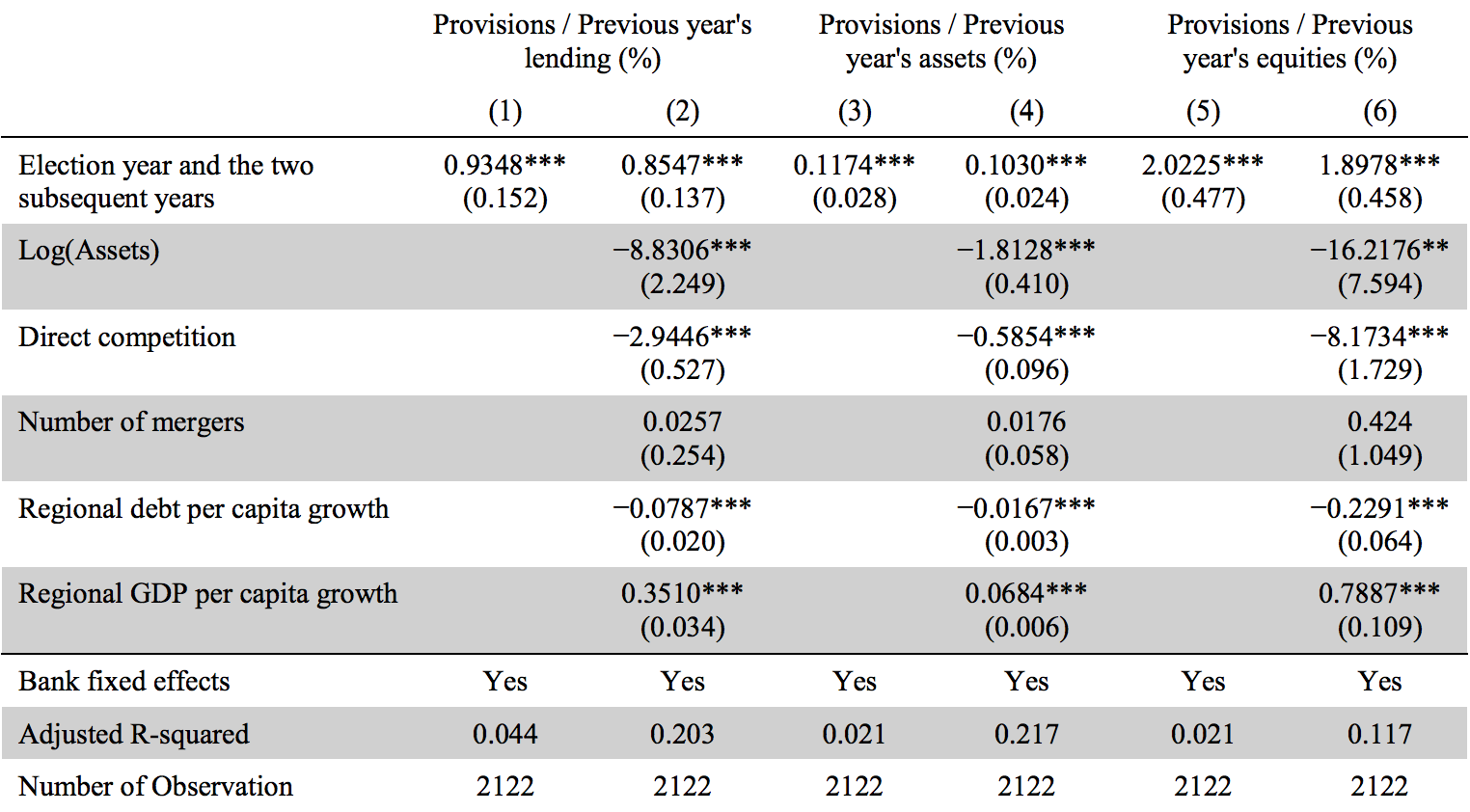

Moreover, our results, presented in Table 4, reject the hypothesis that loss provisions do not vary with the election cycle. We find that banks' loss provisions are significantly higher in the years following an election.

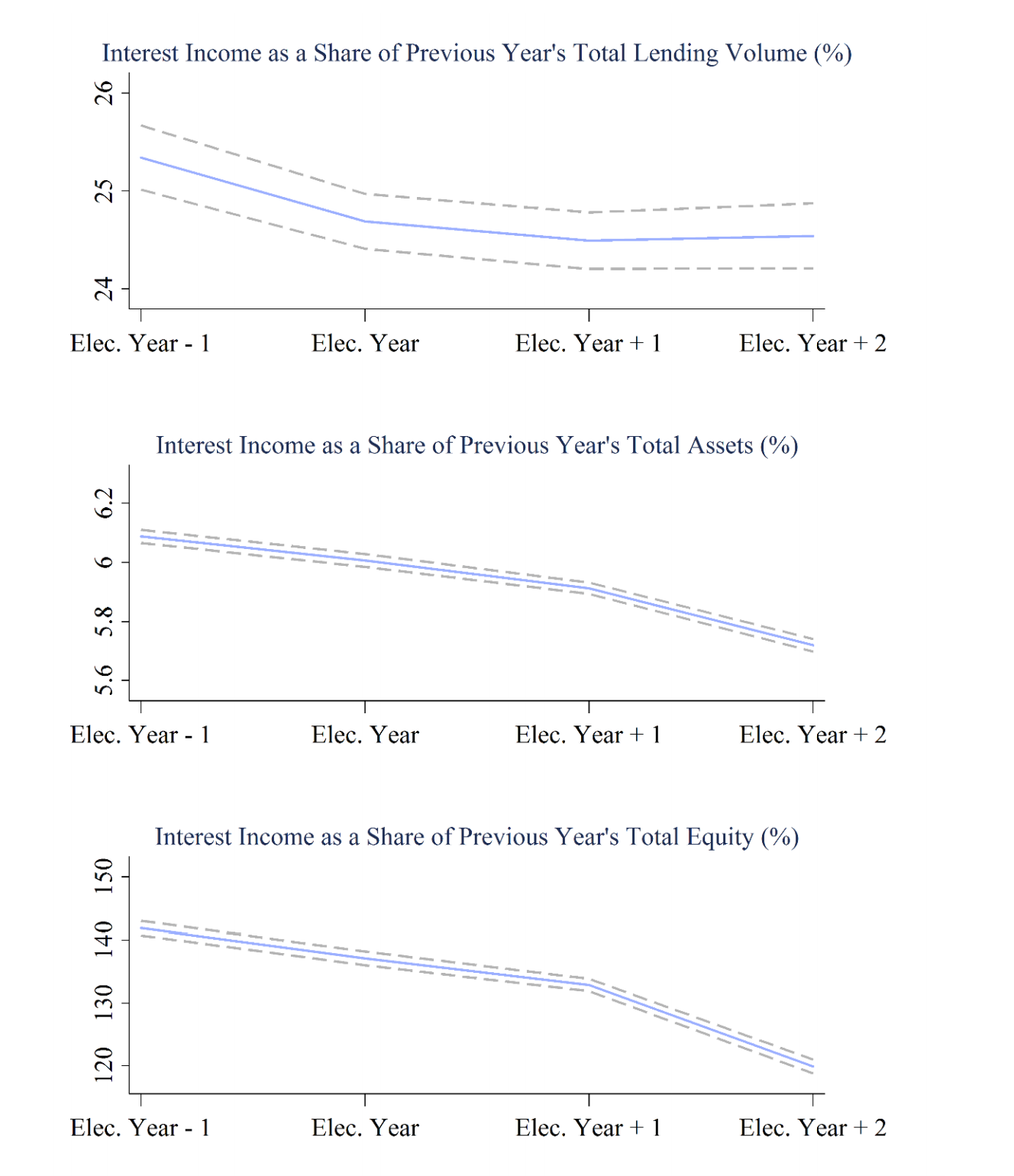

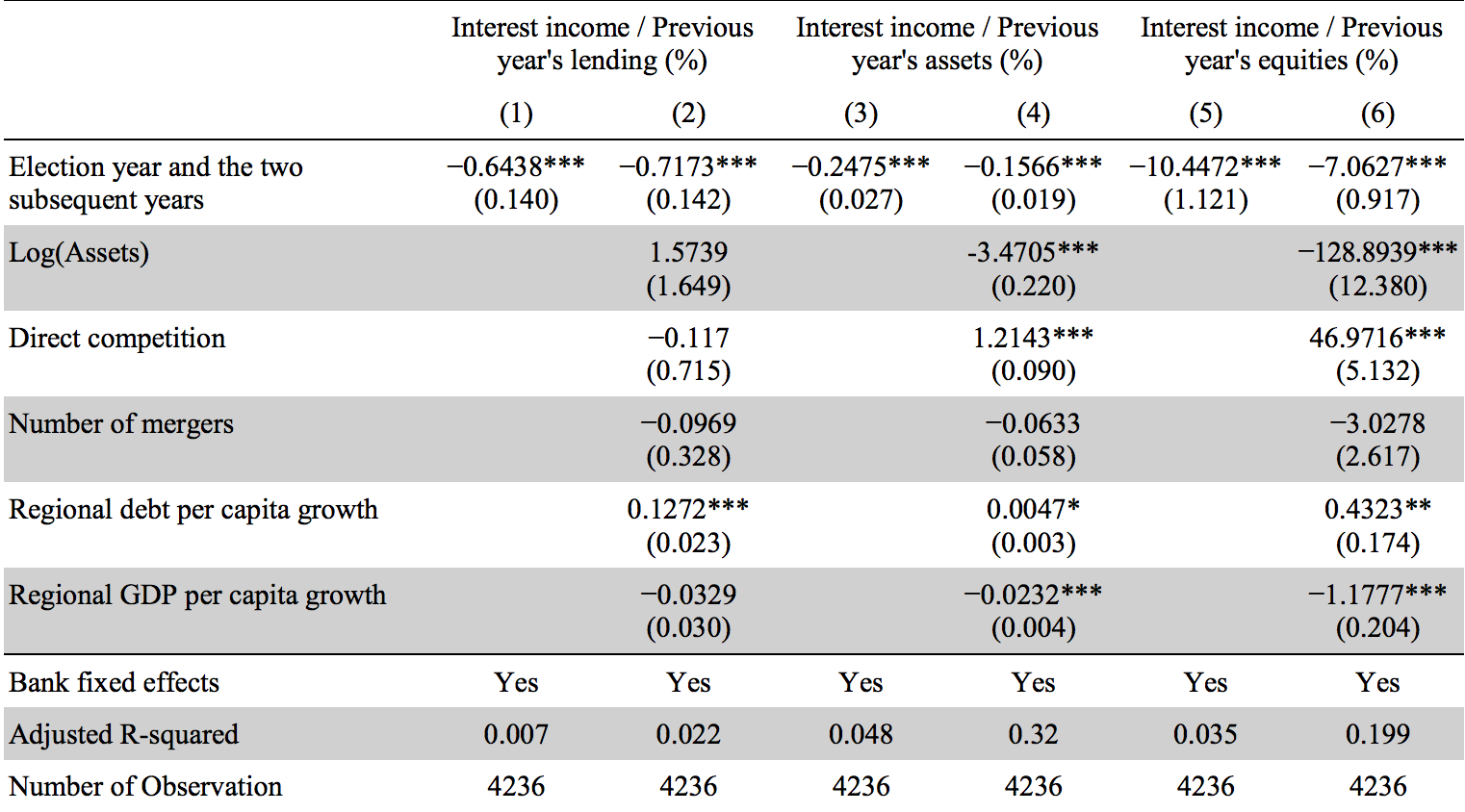

Second, we study total interest income of banks. Figure 3 shows that interest income decreases after election years. All three measures show that banks earn less during and after the election year in comparison to the year just before the election. We estimate the election-year's effect on banks' overall performance in a similar manner as before. The results are presented in Table 5. Interest income per Euro of the stock of loans in the previous year is 0.7 cents lower. Considering that the average amount of new commercial loans is €0.52 billion, this result implies that the average bank loses about €3.6 million of interest income per year during the election year and the two years afterward.4

Figure 3: Interest income during election cycles

Source: Own calculation by using German savings banks’ data

Table 4: Political lending’s effect on banks’ risk taking

Source: Own calculation by using German savings banks’ data

Table 5: Political lending’s effect on banks’ interest income

Source: Own calculation by using German savings banks’ data

Conclusion

The local restriction of activities, combined with the substantial influence of local politicians on savings banks' credit decisions, suggests that the use of banks for political purposes is possible. Our empirical results show that politicians actively make use of their position to their own political advantage by granting more loans and loans at more favourable terms in the year when elections in their community take place.

To avoid political lending in the future, the governance of savings banks has to be improved.

The governance structure of German savings banks may hence induce political lending cycles, a misallocation of capital and also result in distortions of the electoral process. To avoid political lending in the future, the governance of savings banks has to be improved. A possible solution could be to occupy prominent positions within the board of directors (Sparkassenverwaltungsrat) and the central credit committee (Kreditausschuss) with independent experts.

References

Akey, P.: Valuing Changes in Political Networks: Evidence from Campaign Contributions to Close Congressional Elections, Review of Financial Studies, 28, 3188-223, 2015.

Carvalho, D.: The Real Effects of Government-owned Banks: Evidence form an Emerging Market, Journal of Finance, 69 (2), 577-609, 2014.

Englmaier, F.; Stowasser, T.: Electoral Cycles in Savings Bank Lending. Munich Discussion Paper, No. 2014-14, 2014.

Haselmann, R., Schoenherr, D.; Vig, V.: Lending in Social Networks, Unpublished Working Paper, 2014. Khwaja, A. I.; Mian, A.: Do Lenders Favor Politically Connected Firms? Rent Provision in an Emerging Market, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120 (4), 1371-411, 2005.

Nordhaus, W. D.: The Political Business Cycle, Review of Economic Studies, 42 (2), 169-190, 1975. Sapienza, P.: The Effects of Government Ownership on Bank Lending, Journal of Financial Economics, 72, 357-384, 2004.